Innovative Edinburgh Napier research questions how homestay tourism – when travellers stay with locals in their homes – can help rural communities grow their economy.

Date posted

26 January 2017

15:00

Last updated

19 March 2020

Jyoti Sood, who is currently an affiliate at Arizona State University, worked alongside Paul Lynch and Constantia Anastasiadou, both from Edinburgh Napier’s Business School, on the study.

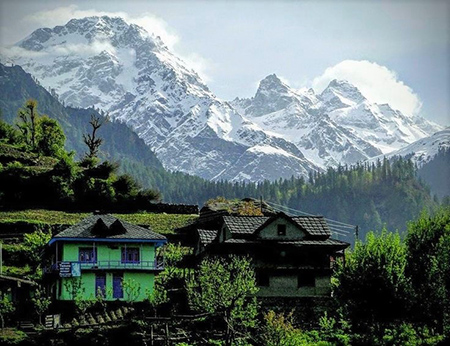

Their research focuses on tourism in the Himalayas but its conclusions are relevant to developing areas across the world.

Why homestay tourism?

The goal of encouraging tourism in developing rural areas is to provide sustainable livelihoods to the local population. Tourism permits diversification away from agriculture, which is often the sole economic activity in these communities.

But tourism can bring new problems.

In the Himalayas, a key issue is the protection of the natural environment including endangered wildlife such as snow leopards. As a result, the area was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014. Homestay tourism avoids the need for hotel construction and other large, disruptive infrastructure projects. This limits the environmental impact of tourism.

Economic and environmental sustainability has made homestay tourism a favoured policy in many developing regions.

Why isn’t homestay tourism happening already?

It isn’t easy to switch from farming to running a service-based business. With little tradition of managing a non-agricultural business, there’s often a lack of entrepreneurial know-how in remote areas.

There’s also a lack of self-belief.

Some people in rural communities find it difficult to overcome the view that their communities are somehow perceived as non-modern and ‘backward’.

One study participant said, ‘We can’t provide the comforts that people from the cities are used to. We have ordinary houses and simple lifestyle[s]. They may not like it.’

There are additional cultural barriers to overcome. Some communities may ostracise those who choose commercialism over traditional practices.

‘Only people who are blatantly driven by money and have spare houses can allow unknown strangers to stay in their house, but the entire village would stop talking to them if the deota [deity] gets offended or a mishappening occurs,’ said another study participant.

Infrastructure is another obvious problem.

In some Himalayan communities, for example, many household toilets are located outside. Traditionally, their purpose has been considered impure, and, more practically, wooden structures typical to the Himalayas are susceptible to water damage.

In situations like this, how should communities balance their traditions with the expectations of tourists?

The study suggests that answers to this type of problem should be community-defined and not imposed by external organisations. Otherwise, there is a risk of non-participation and exploitation by non-locals.

What does the research suggest for policymakers?

The research does offer a number of solutions for policymakers hoping to encourage homestay tourism.

Individuals in rural communities require support to get started. Community-led, NGO and government assistance are necessary at different stages. For example, for marketing support in areas with no internet connectivity.

As one study participant pointed out, ‘Where would a poor person like me go to find tourists?’

In addition, financial support in the form of micro-loans can help communities afford the basic upgrades required to host travellers.

Most importantly, the study highlights the need for mentoring.

Homestay tourism has relatively low barriers to entry – after all, limited home upgrades are necessary – but the perceived barriers are high. Through mentorship and networking, rural communities can benefit from engagement and encouragement. Such support fosters self-belief and builds crucial business knowledge in how to manage a homestay enterprise.

Homestay tourism has relatively low barriers to entry – after all, limited home upgrades are necessary – but the perceived barriers are high. Through mentorship and networking, rural communities can benefit from engagement and encouragement. Such support fosters self-belief and builds crucial business knowledge in how to manage a homestay enterprise.

A community-led approach to homestay tourism is vital

In its conclusion, the study points out that there is a danger homestay enterprises might simply evolve into small scale hotels. If this were so, the traveller would be denied the very experience they came looking for and that rural areas are uniquely able to provide.

It is crucial that communities develop their own approaches to homestay tourism, with support and guidance from external organisations. But this support should seek to enforce home-level not hotel-level standards; rural communities have the potential to offer a distinct alternative to mass tourism practices.

When communities are able to determine the development of their own tourism practices, it is likely to result in greater community participation, sustainable growth and a more authentic experience to visitors.

‘Community non-participation in homestays in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh, India’, authored by Jyoti Sood, Paul Lynch, and Constantia Anastasiadou, is to be published in Tourism Management.

(Pictures courtesy of Jyoti Sood)